A new scientific approach

A/Professor Piero P. Giorgi

Research Affiliated with the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies

University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand (CV at the end)

- Introduction

In the last few centuries philosophers tried to define human nature with little success. Some anthropologists have recently studied this issue from the scientific point of view. A few essential references: Sponsel, 1996; Giorgi, 2001 & 2020; Fry, 2007 & 2021 (the complete list of all authors would take 2-3 pages). Their work was necessary to investigate the origin of violence and nonviolence in our society.

But this important information still remains inside the ivory towers of academia.

I am therefore writing this short note because it has become urgent that the public knows about the following: a) who is Homo sapiens, b) the recent origin of violence and c) the possibility of living together in peace. Our survival as a species is at stake.

- These are the good news

# The nonviolent nature of human beings (in the bio-cultural sense, not as genetic determinism).

# The way in which the vast majority of human beings are living now is not normal for our species.

# The existence of a possible alternative – nonviolent, slow, legal and local changes of lifestyle – to avoid a rapid extinction of our species.

While reading this text you will be asked to exit your everyday world and fly high through time and space. It may cause some dizziness, but it is nothing strange or esoteric, just modern science taken seriously concerning its social implications.[1]

- Our origins

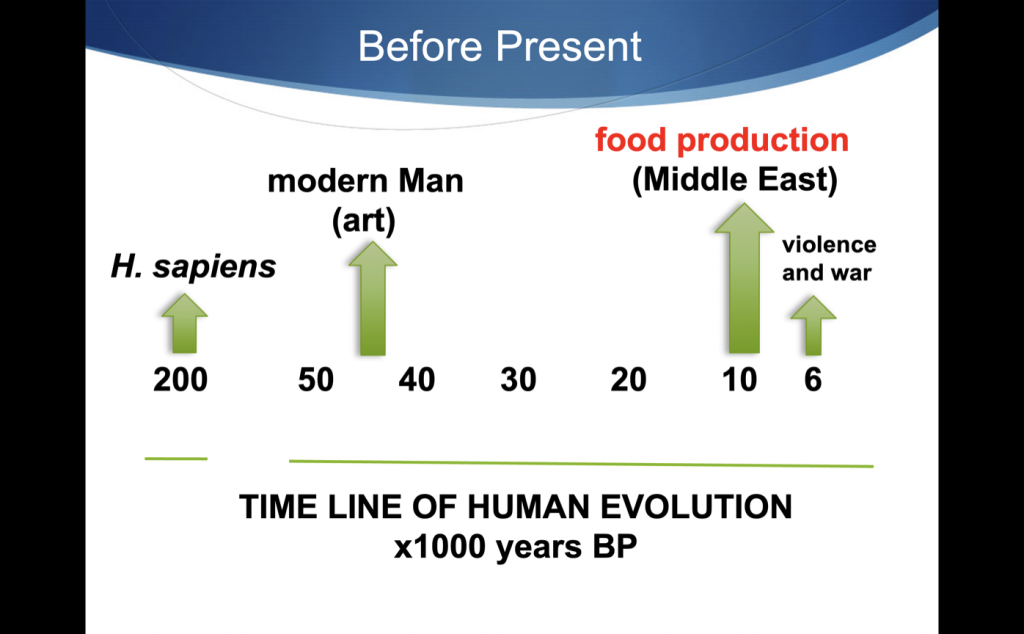

Our species, Homo sapiens, appeared about 200,000 years ago (= before present, BP, see figure below) in Eastern Africa, while the so-called “modern human beings” (those who made art) manifested themselves ca. 50.000 BP (Anati, 2004). In fact, Prof. Emmanuel Anati stated that rock art has added 40,000 years to our history by providing illustrated documents. That is why we have chosen to fly high and start our study of nonviolence with the artistic H. sapiens of the Palaeolithic period, who were also curious and explored all the continents of the Earth, not as recent greedy colonizers did, but as nonviolent nomadic hunter-gatherers, that is as true human beings (see Giorgi, 2020, Section 9.2).

In this short text we will deal with the origin and the growth of two main types of violence: a) violence of human beings against other human beings and b) violence of human beings against nature. They are the main causes of the possibly imminent extinction of H. sapiens if we do not change current trends soon and effectively.

The timeline of human bio-cultural evolution

- The origin of violence

NOTE: Only this section was written by keeping in mind also readers who have some interest in spirituality and religion.

Historically, this is the sequence of events (see also figure above):

# From their initial appearance as a species H. sapiens have been nomadic hunter-gatherers, lived in small communities, and had different forms of spirituality (according to regions and cultures). At the same time, they also had social nonviolence (see Sections 5 and 6) and a great respect for women (Giorgi, 2015a).

# Beginning ca. 10.000 BP, H. sapiens invented (not “discovered”) the production of food in three different and distant regions of the Earth, independently and at different times (by itself a good idea). This practice spread around by cultural imitation (average of 1 km per year). In my view this was the true original sin (see large human settlements below), not biting an apple, as in the legend of the Old Testament.

# Food production caused the loss of nomadism among farmers, but not among nomadic animal breeders.

# Sedentarism plus food surplus caused an exaggerated increase in community size, well beyond the natural need of H. sapiens to live in small communities.

# Large dimensions of human settlements caused professional specialisation, that caused social stratification, then social injustice, then structural violence, marginalisation of women, and war, after a small minority (of men) took power.

# Since then (4-5,000 BP) human beings have been experiencing a considerable social malaise.[2]

# Interestingly, the phenomenon of spiritual prophets appeared only after the onset of violence (in different regions and different cultural settings). Interestingly, their common teaching was as follows: this is not the way people should live(Giorgi, 2015b).

# Unfortunately, after the death of a prophet, in most cases and with different delays, there was a fight among their followers to decide who was to succeed him, just like it was happening with civil powers. This caused a diffuse branching out of different religions and their denominations that became themselves power systems. As such, they obviously had to fight against kings and emperors (the “investiture” controversy) and among themself to retain their own special power. Religious wars remain still today a terrible human shame.

# Recently, political powers and religious powers have learned to make compromises

for reciprocal convenience (the “concordats”).

Ordinary people are still asking to have more spirituality in religion and more social justice in politics. It would be a pity if this improvement had to fail, because a nonviolent H. sapiens was obviously the evolutionary intention of Creation, as prophets reminded us. Perhaps they will be women to lead the necessary cultural changes needed to avoid extinction because of recent violence invented by us by misusing free will (Giorgi, 2015a).

- The nonviolent human nature: anthropological evidence

The art of Palaeolithic H. sapiens (see Section 3 above) is rich, elegant and present in five continents. Most importantly, it consists of millions of images describing hunted animals, gathered fruits and vegetables, images of people and their tools, of spirits and related spiritual concepts, and of sexual relationships, but with substantially nothing related to intraspecific killing before the bronze age (Giorgi, 2001). The very few cases of doubtful interpretation re. possible Palaeolithic intraspecific violence have, interestingly, received enthusiastic reporting by the daily press. That much for ancient Palaeolithic people.

Very importantly, a certain number (ca. 20) of small nomadic hunter-gatherer communities (that is, living like Palaeolithic H. sapiens) have been forced by ancient belligerent cultures to hide in small remote localities on the Earth, and are still living today hiding there. A rich literature written by anthropologists who lived with them last century reported that all of them had a nonviolent culture (Fry, 2007). Many of them are still opposing in this very moment the continuous attempts of local governments that want them to become farmer or to work in towns for a salary like “civilized people”, that is to become structurally violent like us.

- The nonviolent human nature: neurobiological evidence

We all know of mothers who have very rebellious children and say “I cannot do anything about it, they were born that way”. Biological determinism has always been a popular excuse in this field, even in legal contexts and about the weak attempts of preventing violence. But the idea of biological determinism is wrong concerning our social behaviour.

Neurobiologists have known for long time that human babies are born with a very incomplete nervous system: the embryonic neurons are there, but not connected yet. At birth the brain is functionally ready only for important mother-baby interactions.

On the other hand, post-natal interactions are the important factors that define specific connectivity in the newborn baby, during most of infancy and childhood (Giorgi, 2001). This explains a) the high level of complexity in social interactions gained by humans, b) the capacity of accumulation of information from one generation to the next, and c) the origin of empathy and solidarity in our species.

In fact, James W. Prescott has denounced the high degree of physical deprivation among children of modern working women, who enjoy only limited postnatal time for a proper mother-child bonding. This reduces the synthesis of oxytocin by the baby brain and its future capacity for empathy, the important initial attitude to develop nonviolent relationships between humans (Prescott, 1996).

- What can we do to eliminate violence?

In other words: how can we translate neglected good news about human nature and brain functions into practical changes in our lifestyle?

As the question concerns modifications of human cultural traits – not biological traits – the answer must be found in local cultural characteristics, not in general human characteristics. We must, therefore, avoid the unfortunate temptation of changing the world – a chimera used to distract unprepared minds – and concentrate, instead, on practical actions suitable for local cultural situations and local resources.

The need to modify human behaviour and political programs at the local level becomes particularly necessary concerning our violence against nature and the environment. We need to study, to understand dangerous financial interests, corrupted private and public relationships, and unnecessary or dangerous modern practices.

Therefore, one cannot deal in this short introduction with such a complex, fascinating and urgent adventure in local active citizenship. Interested in participating? See below.

- Conclusion

As for many other social problems, education is an important instrument to implement social changes. The nonviolent transformation of society – that is, the recovery of our humanity – implies that we know well the topics summarised in this short paper and we urgently prepare for a slow and local involvement in active citizenship.

If interested in more information, write to pieropgiorgi@gmail.com or read my blog at www.pierogiorgi.org .

In Australia I am organizing meetings and discussions with the hope of passing the baton to younger hands and establishing several local offices of the Association for Nonviolence and Active Citizenship (ANAC). All Friends of Peace are welcome.

References

Anati, E. (2004) La civilta’ delle pietre (The civilization of stones). Edizioni del Centro, Capo di Ponte (Italy). English edition, 2008, same editor.

Fry, D. P. (2007) Beyond war – The human potentials for peace. Oxford University Press, New York.

Fry, P. D. et al. (2021) “Societies within peace systems avoid war and build positive intergroup relationships”. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8, article 17. Open access publication, DOI https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

Giorgi, P. P. (2001) The origin of violence by cultural evolution. Minerva E&S, Brisbane (Australia). This book can be downloaded for free at www.pierogiorgi.org

Giorgi, P. P. (2015a) “The centrality of women in the human adventure” in Mino Vianello & Mary Hawkesworth (eds) Gender and Power – Toward equality and democratic governance, Chapter 9, pp. 154-170. Mcmillan, New York.

Giorgi, P. P. (2015b) “Spirituality and nonkilling – Theoretical basis and practical evidence” in Joam Evans Pim & Pradeep Dhakal (eds) Spiritual nonkilling traditions, Chapter 4, pp. 81-96. This book can be downloaded for free at: www.nonkilling.org/center/publications-media/books-cgnk-publications.

Giorgi, P. P. (2020) La rivoluzione nonviolenta (The nonviolent revolution). Gabrielli Editori, Verona (Italy).

Prescott, J. W. (1996) “The origins of human love and violence”. Pre- and peri-natal Psychology Journal, 10 (3), pp. 143-188.

Sponsel, L. E. (1996) “The natural history of peace. A positive view of human nature and its potentials” In T. Gregor (ed) A natural history of peace, Vanderbilt University Press, Nashville (USA).A/Prof. Piero P. Giorgi holds a BS Hons in Biology (Bologna) and a PhD in Neurology (Newcastle/Tyne). He has been teaching and doing research in biomedical sciences, medical history, and peace studies in six universities of four different countries (Italy, United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Australia). After 25 years at the University of Queensland, during his retirement in Australia he is continuing to study and teaching about violence and nonviolence. He is currently affiliated to the University of Otago – National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies (New Zealand) and the University of Bologna – Department of Education, MODI (Italy). Contacts: pieropgiorgi@gmail.com, mobile phone in Australia: +61/ 0422.053442. Blog: www.pierogiorgi.org .

[1] In the years 1960-70s the interesting trend appeared of discussing the social implications of scientific findings, which was encouraged by biologists at the Open University in England (Prof. Steven Rose). Unfortunately, it did not have much success.

[2] See Sigmund Freud’s “Civilization and its discontents” (1930), although the author was wrong about the actual cause of discontent.